Commentary | The language of erasure in African art

The Art Institute's recent exhibition omits more than it reveals, but the artifacts spoke for themselves

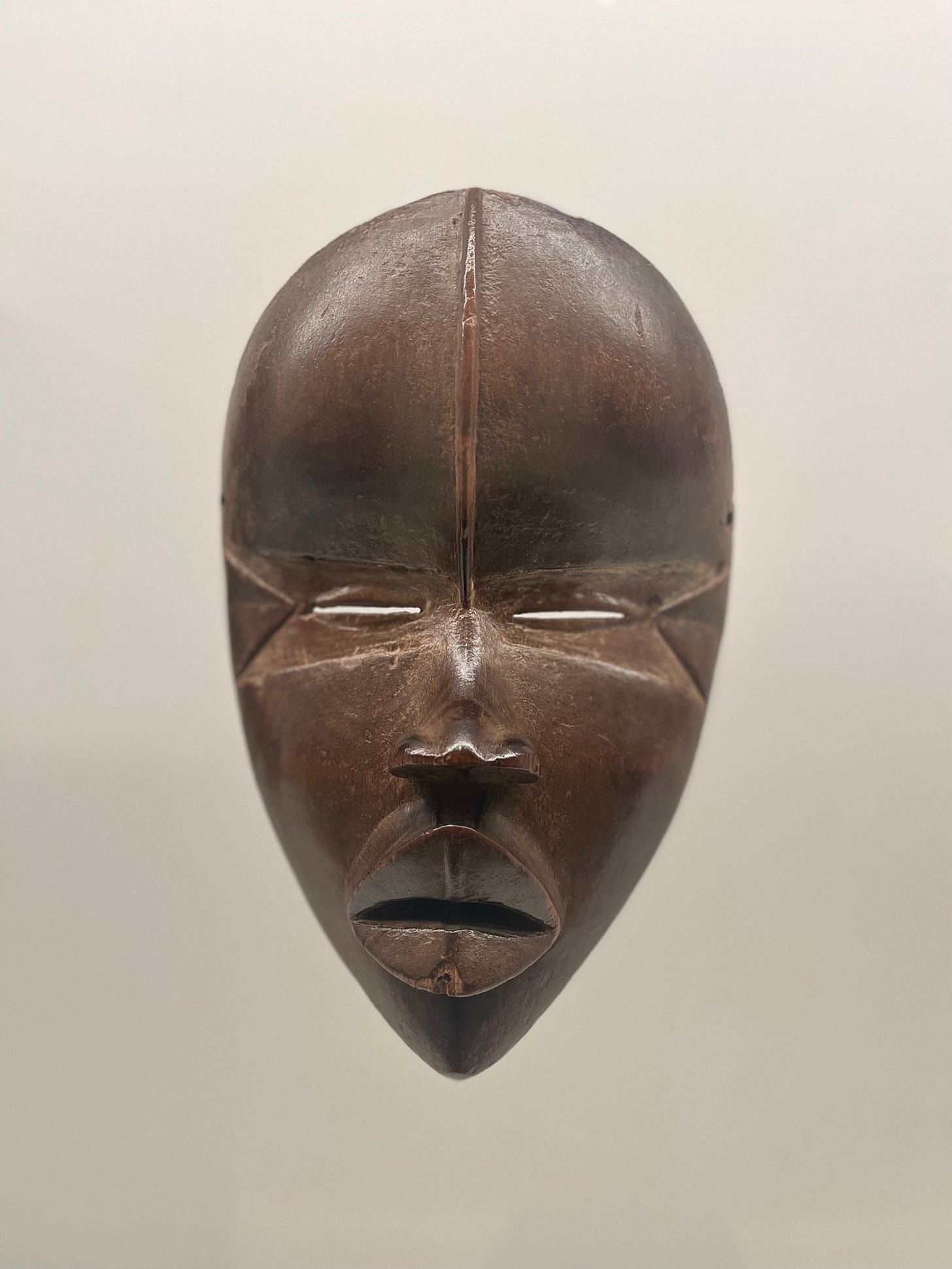

A 20th-century face mask from either Côte d'Ivoire or Liberia produced by the Dan people. Wood and pigment. Private collection, Belgium. Displayed at the Art Institute of Chicago’s exhibition, “The Language of Beauty in African Art.” | Photo by Michael Romain

Last month, I visited the Art Institute of Chicago’s exhibition, “The Language of Beauty in African Art.” An African hair pick caught my eye. I stared at it, transfixed.

In my elementary school youth, I, along with millions of other young, Black males, proudly wore Afro combs similar to the 20th-century one behind the glass. We called them picks. This was in the early 2000s, the Age of Allen Iverson, decades after the pick’s emergence in American iconography during the Black Power era of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Our pick was less the political symbol of Black Power or an assertion of Black Pride than an accoutrement that embellished our youthful, individualized, hyper-consumed swagger; our tacit consciousness that we were the symbols of Hip Hop cultural hegemony, arguably peaking right along with its master, American hegemony.

The pick was also utilitarian — a means to an end. We would incessantly flick the hair tool through our afros before their transformation into intricately sculpted cornrows. Again, this was the Age of Iverson. We were, like him, arrogant and proud without needing to assert Black Pride. We knew the world wanted to copy us, to swagger jack, but we paid the world no nevermind.

But the pick, a potent symbol of Blackness, also symbolizes the attendant existential hazards of being a Black man. The West deifies bombast, confidence, pride and arrogance in white men but renders those values dangerous if present in us. So to protect ourselves, we (those of us with bourgeois aspirations at least) modify our speech, cut our hair, smile and wear masks, masks that are inversions of those created by our Diaspora kin, the Dan people (see the one above). And while in public, we hide our picks.

Jan. 7, 2023. Tyre Nichols, a Black man, is savagely beaten by Memphis police officers, five of them Black men. After Nichols dies three days later, those five Black officers slip seamlessly into a social infrastructure cast precisely for them. Having evaded the more infamous school-to-prison pipeline, these bodily objects are delivered by the less infamous police-to-prison pipeline.

There is a saying among Black folk that ‘Black men are an endangered species.’ Being Black alone is dangerous enough. But to be Black and male, regardless of which side of the thin blue line you may stand on, is a hazard of another order. Museums are spectacles of endangerment, where the extant go to pay their respects to the extinct or the near-extinct. These are my thoughts in the museum as visitors crane their necks in wonderment around me.

Chokwe, Angola or Democratic Republica of the Congo, Haircomb, 19th century, wood, pigment, glass beads, and fiber. Displayed at the Art Institute of Chicago’s exhibition, “The Language of Beauty in African Art.” | Photo by Michael Romain

“While fashions have changed dramatically over the last century,” explains the curatorial description underneath the hair pick, “ornamental combs like those displayed in this case offer a hint of the incredible variety of hairstyles, adornment, and styling techniques that were popular around the continent to signal rank, wealth, stage of life, beauty or good health. In the Yaka and Chokwe cultures, both men and women wore decorative haircombs. The double hornbills on one shown here are linked to hunting and the related power of Chokwe leaders. The upturned, snout-like nose depicted on the Yoka implies the power of the male wearer, while the hairstyle and hat are used exclusively by chiefs and dignitaries.”

Despite the curator’s dry tone of neutrality, I do not see this 19th-century hair pick as a mere museum piece. I see the pick of my youth and the ancient accretions of Black Diaspora creativity dating back thousands of years that went into making me what I am.

The museum’s dispassionate, clinical description of the African “Haircomb” and other pieces is upsetting because these artifacts, gained through plunder and looting, are aspects of my Black being that were systematically erased. Most pieces have no attribution because Europeans did not inventory them during their scramble for Africa’s wealth.

This hair pick, reminiscent of one used by the author in his youth, was manufactured by Eden Enterprise, Inc. The pick has a black molded plastic handle shaped like a raised fist. The teeth of the pick are metal. In relief on the front of the plastic handle is text that reads "Eden/ Christina MJ/ MADE IN CHINA." Circa 2002-2014. | Creative Commons via National Museum of African American History and Culture

In fact, the entire exhibition was upsetting in all its quiet majesty and searing beauty. The Art Institute’s good-faith attempt to celebrate these African artifacts on African terms is undercut by the museum’s glaring omission of the brutal fact of their being there. The museum acknowledges this underlying brutality in a vague and roundabout way on one wall.

“The collecting of African objects in Europe and North America accelerated in the early 20th century. Over the last few decades, institutions across the globe have increasingly scrutinized the circumstances surrounding the acquisition of African objects, particularly during colonization, and the Art Institute is an active partner in these ongoing efforts. We recognize the urgent need to identify works that were seized or have contested ownership and, through projects such as this one, aim to further the conversations about cultural representation and responsible museum stewardship that are taking place around the world today.”

This is such masterful evasion. The “collecting” of these objects in the West “accelerated.” How were they collected? What prompted the acceleration? And to say they were “seized” implies a police action, as if the objects were gained by law enforcement in a sting operation on some ghetto crack house. The curator’s language studiously avoids describing what, in truth, happened.

Jan. 20, 1897. Rear-Admiral Harry Rawson leaves a British naval base near Cape Town on board the St. George. He is on a mission that will take him to Benin City in what is now Nigeria to conduct, in the words of the English bard Rudyard Kipling, one of Britain’s many “savage wars of peace” (an Orwellianism that reminds me of the Scorpion unit that killed Tyre, Scorpion being short for Street Crimes Operation to Restore Peace in Our Neighborhoods).

Oba Ovonramwen, the leader of the Benin kingdom, had punctured the perceived prerogative of the British to monopolize the trade of Benin’s valuable rubber and palm oil, essential to the Industrial Revolution and the profits of the Niger Coast Protectorate.

The Oba, acting within his authority as sovereign, refused to allow the British to increase exports of Benin’s palm oil, so the British decided he had to go. Rawson led a Royal Navy expedition that included his “squadron, six cruisers and smaller gunboats,” and West African soldiers from rival ethnic groups, writes Barnaby Phillips in “Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes.”

By the middle of February, Rawson’s mission is accomplished. After slaughtering Benin’s Edo people and forcing the Oba into exile, Rawson’s men plunder the Oba’s palace and take off with the famous Benin Bronzes, elaborate sculptures that narrate the history of the Edo people. While there were no Benin Bronzes on display in “The Language of Beauty,” the Art Institute does have two of the ill-gotten pieces in their permanent collection, the Chicago Tribune reported.

A display of Benin Bronzes at the British Museum. | Joy of Museums/Wikimedia Commons

“For the British, [the Bronzes] were instruments of the Oba’s power and the practice of human sacrifice, both of which they were determined to end,” Phillips writes. “They did not bother to record how many pieces they took, where they found them within the palace, which pieces belonged to which altar, or the relative position of shrines or altars. It was a moment of vandalism, a rupturing of tradition and knowledge, that scholars of Benin’s art and history have spent many decades trying to repair.

“The officers posed for photos, surrounded by their booty. They look tired and dirty, but satisfied, just as a white hunter looks pleased holding up the head of a fallen buffalo, or with his foot on a dead elephant. […] Already, seeing the amusement in their eyes, one can almost hear the questions which would be asked again and again in the coming years: ‘Who would have thought they [the Edo people of Benin] had all this fine stuff? And, their faces betraying little smiles of incredulity: ‘Surely they didn’t make this themselves?’”

Once back in England, the British soldiers would distribute the loot to western museums and private collectors. Now, imagine this savage cycle of slaughter, vandalism, looting and erasure repeating across the African continent for decades and by multiple imperial powers like Germany and France during the years of western colonialism.

In 1960, 17 former African colonies took their independence and gained membership in the United Nations, and more and more Africans began demanding that Europe return what had been looted.

“Fearing the loss of this very African culture — at least, in its material form — the former colonial powers of Belgium, France and the United Kingdom began to protect their own museum collections immediately after 1960,” writes Benedicte Savoy in “Africa’s Struggle for its Art: History of a Postcolonial Defeat.”

“To shield themselves from restitution demands and to legally safeguard the ownership of collections amassed in museums in Brussels, Paris or London since the nineteenth century they used varying strategies,” Savoy writes. “Historically, the holdings of the Musée national des arts africains et océaniens in Paris were under the stewardship of the Ministry of the Colonies but in 1960, they were transferred with the stroke of a pen to the impenetrable Ministry of Culture and thus confirmed as part of France’s inalienable national heritage.”

Africans have been asking for their stuff back for roughly a century (the Edo people have been asking since at least the 1930s). The demands only crystallize what western museums like the Art Institute would rather omit: the only “responsible museum stewardship” of these African artifacts is to remove them from western museums and return them to their rightful owners.

Interior of Oba's compound, burnt during seige of Benin City (present day Nigeria) , with bronze plaques in the foreground and three British soldiers of the Benin Punative Expedition on Feb. 18, 1897. | Photographer Reginald Granville./Wikimedia Commons

As I walked through the Art Institute’s exhibition, I could not help but link the curatorial elision and erasure to the ethnocide that rendered the Chokwe hair pick a museum spectacle. As Aimé Césaire articulated at the First World Congress of Black Writers and Artists in 1956:

“One cannot raise the problem of black culture today without raising the problem of colonialism, since all black cultures at present develop in this particular condition, where they are colonial or semicolonial or paracolonial,” Césaire said.

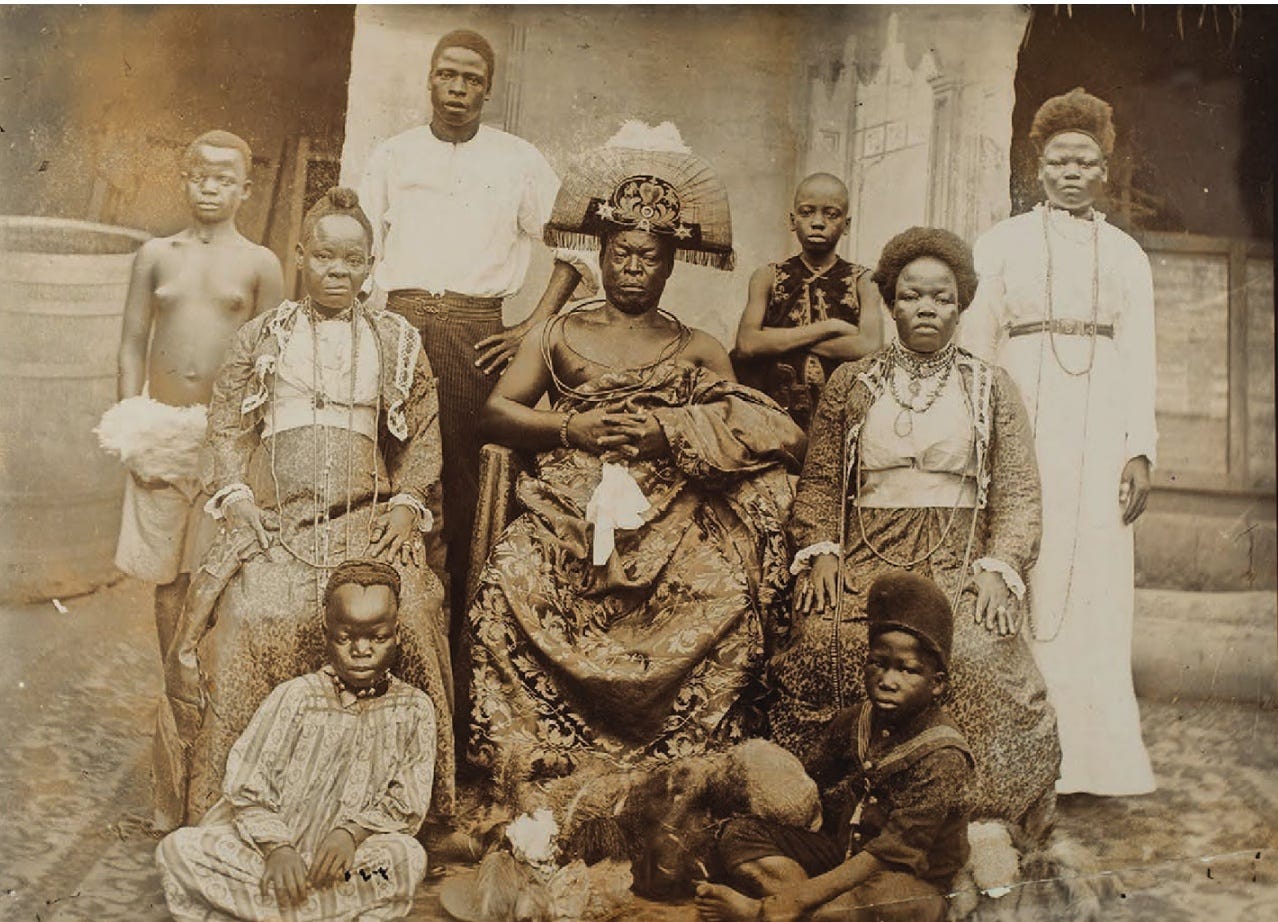

Oba Ovonramwen with his two wives in exile in Calabar, circa 1912. | Wikimedia Commons

This echo of racial colonialism resonates across centuries and geographies. It resonates across social contexts. It resonates today.

“Europe would have done better to tolerate the non-European civilizations at its side, leaving them alive, dynamic and prosperous, whole and not mutilated,” Césaire writes in his influential 1950 essay, “Discourse on Colonialism.”

“That it would have been better to let them develop and fulfill themselves than to present for our admiration, duly labelled, their dead and scattered parts; that anyway, the museum by itself is nothing; that it means nothing, that it can say nothing, when smug self-satisfaction rots the eyes, when a secret contempt for others withers the heart, when racism, admitted or not, dries up sympathy; that it means nothing if its only purpose is to feed the delights of vanity … No, in the scales of knowledge all the museums in the world will never weigh so much as one spark of human sympathy.”

Thank you for reading this newsletter. I enjoy writing this and will happily send aspects of it free to readers. But this writing is hard and takes an emotional and intellectual toll. If you enjoy reading and would like to support, please consider subscribing.

So glad I got a notice from Substack that you writing here. I open the shell of what's left of the Wednesday Journal and feel a loss every week.

I had promised not to become a paid subscriber to any more Substacks but I have broken my word. (shhh.)